The castle of the metamorphoses is bound to hold opposites together. Ancient, it looks forward being hypermodern. Rational and technological, it cultivates the unconscious and the primitive. Its aesthetic references are the 20th century avant-garde art movements that have drawn their inspiration and their models from the so-called primitive art.

The collections include masks and totem poles of the Pacific Northwest Coast Indian tribes, African masks and ritual objects, works by artists who rely on discarded or reclaimed everyday life objects. All collections share a reflexive or problematic attitude towards metamorphosis and change. They confront themselves with different patterns of transition from one state into another. They mirror the pictorial narratives of the Ovid-inspired frescoes. They echo the hybrids and the bizarre entities dwelt in the grotesques.

The Art of the Northwest Coast

The several thousands miles stretch of land and sea between the Strait of San Juan de Fuca (north of Seattle) and Alaska hosts dozens of native settlements that have survived the brutal assimilation organized by the United States, and even more so by the supposedly enlightened and tolerant Canada. Children were abducted from their families to be confined and reeducated in the so called “residential schools”. Potlatches were prohibited and their clandestine organizers were prosecuted. Thousands of ritual objects were seized and sometimes destroyed in the attempted eradication of tribal cultures, non-Christian religious rituals, and so on.

In the last few decades, the communities of the First Nations (the Canadian designation for the Indian and Inuit populations) have begun a strong, proud and public recovery of their cultural identity, and the display of the forms and objects that portrayed it. The explosion of a strong interest for native art in the contemporary art world has been a cause and effect of this recovery.

The Castle holds a significant number of wooden sculptures and artifacts carved by some of the most interesting native artistsof the last generations, often but not always born in the trade, their fathers having been renowned carvers: Art Thompson, Beau Dick, Ron Telek, Douglas David, Tom Hunt, Merwyn Child, Wayne Alfred, etc.

Many of the distinctive styles of the different ‘nations’ are represented. Contiguous communities often displaywidely diverseartistic languages, and sometimes the diversity runsthrough the products and artifacts of a single ‘nation’. The collection allows the spectator to appreciateboth the unity and the differences. It displays works from most of the major tribal bodies: the Tlingit, Haida, Tsimishian, Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Nisga’a. Styles are sometimes typical and pure, but hybrids and contrasting influences keep lurking behind many carvings.

The wooden masks are linked to ritual functions or mythical-religious symbolism: the cannibal bird Hukhuk and the version used for their initiation dance by the Hamatsa, the most important of the Kwakwaka’wakw secret societies,; the Dzunukwa, or Tsonokwa, or Wild Woman; the Bakwas’, or the Wild Man of the woods; the masks expressing the shamanic possession; the comical masks used to mock or create laughter during the ritual performances; Ganhada, the trickster Raven which governs and transforms all things.

Each carving condenses a story. Each is the subject and character of multiple narratives that intertwine myths of the Nation and of the community, clan events, family variations, and, more rarely, the advent of individual heroes. A face-to-face contact with a carver often is a remarkable experience: obviously he wants to sell, but perhaps above all he wants to tell stories. He can do it for hours in the rain and in the cold, using a given sculpture as an excuse. We experienced it at length in Alert Bay, inside the Beau Dick’s shed, and with Stephen Bruce, and Wayne Alfred, etc …

The totem pole is a rather peculiar ritual object, often organized as a vertical narrative, and as a sequence of transformations. In a given example, the basis of the pole – a bear – turns into a killer whale (2nd level), which turns into Dzunukwa, then into Raven, then again into the hero/chief, and ends into the Copper (the symbol of the chief’s power). The castle is home to two totems of rare beauty. The first one was carved out of a three-meter red cedar trunk, a masterpiece by the much regretted Art Thompson, who completedit just before his death. It tells of the metamorphosis leading to the birth of Pook’ubs, the human being whose existence is suspended between the living and the dead, between the animal realm and society, with his open mouth about to tell a story. The second one, by Stephen Bruce, a Kwakwaka’wakw from Alert Bay, is a welcome totem. This nine-meter pole carved out of a single red cedar trunk extends its powerful arms to engulf the newcomer and hug him into the community through Dzunukwa and the Hero/Chief. It was included in the joint exhibition, The Power of Giving, held in Alert Bay and in Dresden, with the U’mista and the Staatliche Kunstsasmmlungen of Dresden as the curators. Its picture fills the cover of the exhibition’s catalogue.

The reinvention of tradition is a complicated undertaking. Nearly all of the “native” artists underscore in their biographies how much they are and always were embedded in their community. The works that they produce are humbly or proudly described as an emanation of the spirit and the identity of their nation. It obviously isn’t so. Critically observed, the collection assembled in the castle betraysthe difficult connection between each work and the underlying canon, between the prescribed model and the individual achievement. But it captures even more another issue. The artists of the Northwest Coast claim that they produce their pieces in the name of and on behalf of their community, but in fact they sell them in cities like Vancouver and Victoria, where most of them live a somewhat hidden life. As for the 19th century totem poles, the tradition is largely reinvented as a commodity for sale to strangers and visitors. It is first reenacted to be sold, and then rediscovered as a possibly authentic layer of a collective identity. The stage conjures up a new-‘old’ reality dubbed as an origin.

The collection of artifacts is paralleled with thousands of images of ancient and contemporary totems that have been gathered in over 20 years of travel, in often hard to reach places, throughout the Northwest of USA and Canada. The archive is available for consulting through the terminals located in the castle. It allows you to observe the varying attitudes of the tribal communities towards the natural history of the poles (how they age and die), their different styles, the emergence of new modes and functions, the impact of modernization and market demand, the differing meanings and sometimes the loss of meaning caused by reinventing a tradition detached from the current reality of the so-called First Nations.

In counterpoint, another collection of ritual objects from the Southwest (Arizona, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico) underlines the originality of art forms produced 6,000 km further north.

The Masks of the Padiglione Collection

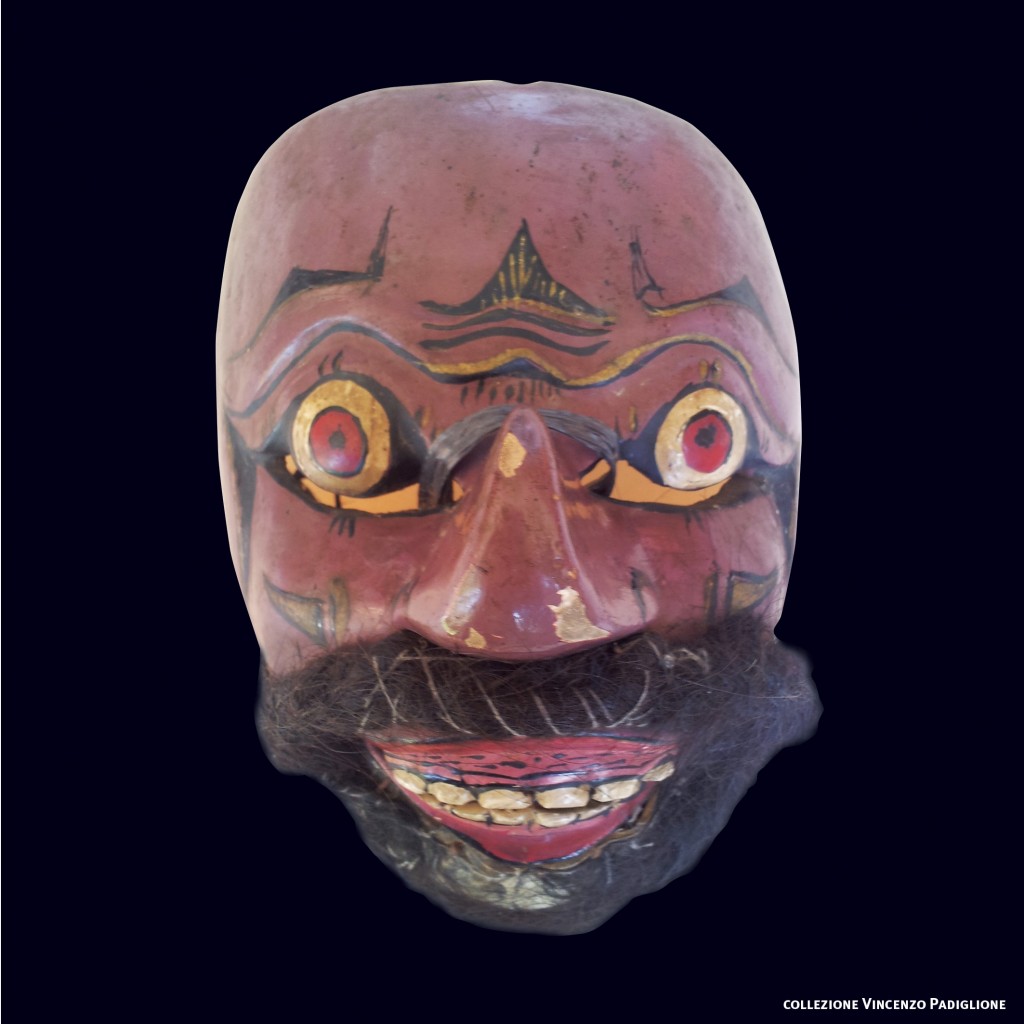

The castle hosts the collection of Vincenzo Padiglione, an anthropologist and curator of several ethnographic museums in the Lazio and Rome areas. This collection assembles over 500 exotic, western, souvenir, ritual, play, work, traditional and contemporary masks.

Plain, simple, even humble, and at times exceedingly complex. Most of them were worn somewhere by someone. Lively and lived. Surprisingly beautiful, with lots of freshness surfacing through the scars of time and usage. Masks belonging to the road, not the museum.

This collection originates in two decades of extensive ethnographic research: from the classic field work to tourist art, from the artisans’ workshops to the flea markets, from the homes of collectors to the mats resting on the ground in the streets.

The first fil rouge is the fantastic. Seen all together, these masks invite to a journey into chaos. They nurture a parallel world made out of a hybrid humanity, composites of humans and animals, anthropological mutations, chimeras. Their concrete morphings outline our potential evolution towards future forms, or our regression towards forms that we were who knows when and where.

The other thread is a face-to-face encounter with diversity: somatic, physiognomic, at the same time entirely biological and entirely sociocultural and historical. These masks ask us to get in touch with the many possible identities that live their often invisible life within us and around us.

It would be comforting and reassuring to think those masks just as carnival or theatre items, belonging to the surface of reality.

The Padiglione collection forces us to recognize them as changing cores of our identity. This is why it has chosen to find a home, or maybe a shelter, in Rocca Sinibalda, in the castle of the metamorphoses.

Three powerful female figures stand in a circle at the centre of the Great Hall, and of the rationality of his panopticon: Vulcania, Amazon, and Angela. Their primitive forms are a hotchpotch of all kinds of heterogeneous materials. Rust, pieces of machinery, sharp metals, chains, plastic, wire, ropes, and much more inorganic materials build up bodies overloaded with sensuality and explicit eroticism, with desires and prohibitions. Three Fates, a Faustian Realm of the Mothers, embody at the very centre of the Castle its dark soul, made up of the unconscious and the imaginary. An intimate heart of darkness that comments, translates, and discloses the anti-Renaissance stance of the castle, its dark side, the wild animal hiding in its zoomorphic identity. While gazing at them, the abstract geometryof its architecture disappears, together with itsfunctional rationality as a war machine.

Their creator is Marcos Cei, an Italian-Argentine sculptor who presently lives in Paris, and dreams of taking refuge in Portugal. For a long time, he has been a jack-of-all-tradesat the Darthea Speyer Gallery, in Rue Callot, and an intermittent bouquiniste on the Quais. He personally brought the three “demoiselles” to Rocca Sinibalda and placed them where they are now. More weird Mothers should follow soon